The letter came on a Tuesday in a dull brown envelope that looked like all the other boring paperwork in the world. But inside was the kind of sentence that makes you feel like you can’t breathe: “Amount due to the State on succession.” Anna looked at the figure. Her father had worked for forty-two years. She had held his hand while he was in the hospital. The tax bill was now more than what her teenage son would get from the same inheritance. She read the letter three times. I called the notary. Sat quietly on the edge of her bed with her phone in her hand, wondering how the State could take more than just her family.

Most people don’t read the rule that gives the weird answer until it’s too late.

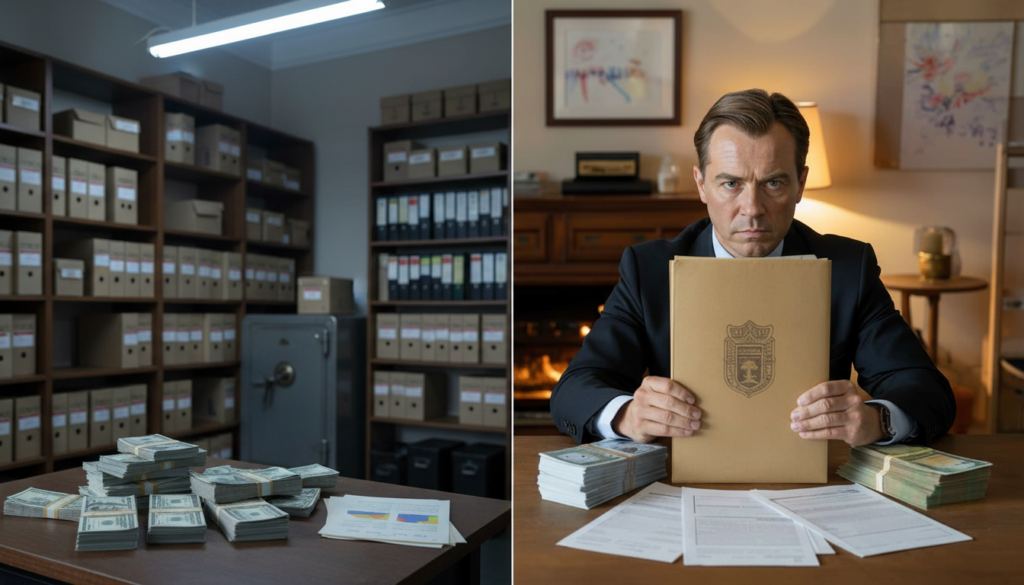

The rule that hurts grieving families the most

Let’s start with the part that no one wants to think about: who gets your money when you die. It looks easy on paper. You work hard, save money, and give it to your kids. In real life, a cold, technical rule often sneaks in: inheritance tax rates that go up as soon as you leave the “right” family box.

People are shocked when they find out that the government can take so much money that their own kids, or the kids they raised as their own, end up with less than the tax office.

Marc, who is 64, was with his partner Julie for twenty years. They never got married or signed a civil union. He would joke, “We didn’t need a piece of paper to prove we loved each other.” He helped her raise her daughter, paid for school trips, fixed the bathroom that was leaking, and made pancakes on Sundays while wearing his robe.

His savings and small flat went to Julie and her daughter when he died suddenly. The numbers on the notary’s desk got ugly. The tax rate went up a lot because they weren’t legally connected. On paper, the child he always called “my girl” was treated like a stranger. The state had taken a bigger bite than the girl who put his picture on her bedside table by the time the bill was paid.

The tax systems work like a popularity contest, putting heirs in order of how much money they have. Spouses and biological or legally adopted children get the best treatment. Stepchildren, long-term partners, nieces, nephews, or friends can all end up in the highest tax brackets, where they have to pay very high rates and get very small allowances. The “controversial rule” isn’t just one sentence in a law. The law decides who is and isn’t “family.”

On a spreadsheet, the logic is “fair”: the closer the family member, the less tax. In the real world, where families are mixed, divorces happen late, same-sex partners are common, second chances are common, and unofficial parenting is common, that logic seems cruel. The State is better protected than the child you raised.

How to keep the State from being your biggest heir

The first step is very boring, which is why so many people put it off: sit down and draw a map of your real family, not just the one on official papers. Who do you really want to keep safe? A partner you never married. A stepchild you’ve known since they were a baby. A brother or sister who put everything else on hold to help you. Write down their names on a piece of paper, and then see which ones the law actually recognises.

Once you know that, you can start changing the frame. This could include marriage or a civil union, adopting a stepchild if you can, getting life insurance, giving gifts while you’re alive, and making a will. Every move you make moves money away from the highest tax brackets and closer to the people you care about.

The most common mistake is to wait for the “right time.” People tell themselves that they will deal with it after the next promotion, the next move, when the kids are older, or when the divorce is final. Then a stroke, an accident, or a bad diagnosis comes along and doesn’t care about your schedule. Let’s be honest: no one really looks over their estate planning every year.

Garden centers dislike this resilient plant because it makes many decorative flowers unnecessary

Garden centers dislike this resilient plant because it makes many decorative flowers unnecessary

That’s why a good afternoon of paperwork can change everything. Not great planning. Just enough to stop the rule from being the most harsh. Even if it’s just for a short meeting, talk to a notary or estate lawyer and say what you really want: “I don’t want the State to take more than my own children.”

We’ve all been there: the time when you tell yourself you’ll “sort it out later” and hope that later never comes. A notary I talked to said, “The worst inheritance cases I see are almost never about money.” They are about waiting and being quiet.

The law doesn’t wait for families to get their feelings in order.

Write a simple willA simple, legally binding will makes it clear who gets what and keeps your assets from going to distant relatives or the highest-taxed paths by default.

Use life insurance wiselyIn a lot of places, the tax rules for life insurance payouts are different than those for direct inheritances. This can be much better for partners or stepchildren.

Give small gifts while you’re alive. Regular, moderate gifts during your lifetime can slowly move assets to the next generation, often with little or no tax, and you can see your loved ones benefit.

Make the ties you already have official. When possible, marriage, civil partnerships, or adopting a stepchild can turn a “stranger on paper” into a protected heir in the eyes of the law.

Don’t try to do your own legal gymnastics. Copying and pasting someone else’s clauses from the internet can backfire. When things get serious, a short meeting with a professional is better than months of guessing online.

What this rule says about who we call “family”

You can see the pattern everywhere once you start looking. The tax code still thinks of families as they used to be: one marriage, shared kids, and a neat nuclear unit. But today, funerals are full of exes, step-siblings, partners who aren’t married, and kids who call three different adults “mum” or “dad.” The law moves slowly, but our lives do not.

The most painful wrongs happen in that gap. Your sister, who slept on your couch while you were getting chemo, gets a tax bill like she won the lottery. You raised a child but never adopted them, so they are like a distant cousin. It’s not just about money that the rule lets the State take more than your “real” family. It’s about being recognised.

This is where the talk changes from maths to morals without anyone noticing. Should the system protect the Treasury first, or the lives that have been built up over decades in small kitchens and crowded living rooms? Some people say that a high inheritance tax is a way to fight inequality and keep fortunes from growing forever. Some people say that small apartments and regular savings also get caught up in the net, hurting families who never thought of themselves as “wealthy” in the first place.

A tired majority stands between these two camps.

They only find out about the battlefield after the funeral, when it’s too late to change the lines.

So maybe the real question isn’t “How do I beat the system?” but “How do I make my paperwork match my life?” You don’t need to know everything there is to know about taxes. You just need to decide who you can’t stand to see punished by a rule they didn’t choose. Then do something real, like make a call, write a letter, or talk at the kitchen table.

You want your name and your wishes to be heard louder than any default formula when the brown envelope arrives. The law will still have a say. But it doesn’t have to yell over your kids if you make a few careful moves.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Map your “real” family | List who you emotionally and financially consider as heirs, then compare with who the law recognises today. | Reveals where the State could take more than your intended beneficiaries. |

| Use legal tools early | Will, life insurance, gifts, marriage/civil union or adoption of a stepchild where possible. | Reduces tax shocks and directs assets towards the people you actually want to protect. |

| Get one professional review | A short session with a notary or estate lawyer to stress-test your current situation. | Flags hidden risks and costly mistakes that DIY planning usually misses. |