It wasn’t a scientist who gave the first warning. A grandma in Ohio yelled at the TV. A suited astronomer calmly explained on the screen that an international team would “slightly reduce incoming solar radiation” to make things safer and better for research during the longest solar eclipse of the century. The living room got quiet. “Are they dimming the sun now?” she said. “That’s stealing in broad daylight.”

The story spread like wildfire across timelines. Gen Z TikTokers yelled “planet-sized experiment,” boomers on Facebook shared blurry conspiracy theories, and tired parents in the middle just wanted to know if their kids could still watch the eclipse from the backyard.

The sky isn’t dark yet, but the split is already here.

When the sun turns into a switch that you can turn down

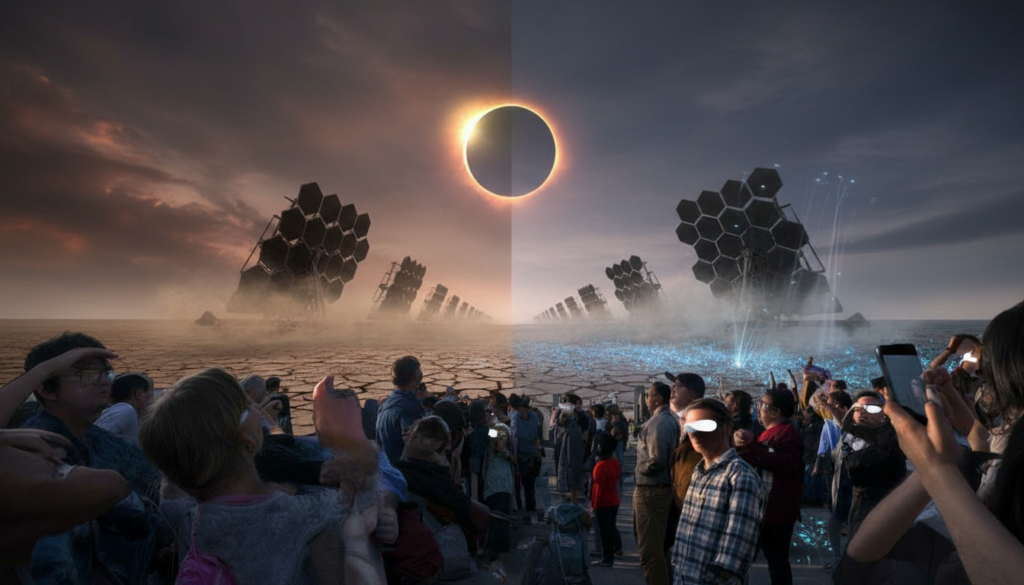

Imagine the sky being clear at noon on the day of the eclipse. People are filling the streets, using cardboard boxes as viewers, cheap plastic eclipse glasses that may or may not be real, and phones pointing up. Now picture huge cargo planes and balloons flying high in the sky for weeks, quietly dropping reflective particles along the path of the eclipse.

Not enough to completely block the sun. Just enough to make it less bright. To make the glare less strong. To change a once-in-a-lifetime event into something that is more “controlled,” easier to measure, and more… engineered.

The moon doesn’t dim the sun; people do.

The plan, as put forth by a number of research consortia, seems almost modest on paper. They want to use the rare alignment as a natural laboratory during the longest solar eclipse of the century. By releasing tiny reflective aerosols at high altitude in targeted zones, they can test how sunlight scatters, how air layers behave, how quickly temperatures shift.

One scientist said in a press briefing that it was like “turning down the dimmer switch by a few percent in a single room of a huge house, just for a moment, to see how the wiring responds.” That “room” is a narrow hallway that goes through several countries. The wires are our sky, our weather, and our air.

It’s less abstract for people who live in that corridor. It’s their choice to make the middle of the day a little less bright.

The logic behind the controversy is very simple. Some people say that if human emissions trap more heat, we might be able to send more sunlight back into space. Geoengineering: a word that sounds like a sci-fi movie script and a legal disclaimer at the same time.

The point of this eclipse experiment isn’t to cool the Earth down for good. It’s a test, a practice run, and a way to collect information for models that could one day help shape emergency climate responses. That’s what the official line says.

But once you accept that people can learn to dim the sun on command, even a little bit, it’s hard to close that door again.

How do you “dim” a star without breaking the world?

The method behind the headlines about “dimming the sun” is both ordinary and very smart. Specialised planes and balloons release aerosols, which are tiny particles, into carefully chosen layers of the atmosphere. Think of volcanic ash, but made in a lab and measured in grams and tonnes instead of mountains.

These particles don’t block the sun like a curtain does. They reflect some light back into space and soften the light that hits the ground. During a long eclipse, when the temperature is about to drop sharply for a few minutes, that small change lets scientists figure out what caused what, almost like a controlled A/B test of the sky.

In simple terms, we’re talking about a very small change in how strong the sun is. In a symbolic sense, we’re touching the untouchable.

The problem is that no one really lives at the “symbolic level.” People live in their bodies, their routines, and their beliefs. When a farmer in Turkey hears that planes “darken the sun” on eclipse day, he doesn’t see a dataset; he sees his already unpredictable seasons being used as a test bench.

Students who are worried about climate change share infographics about the possible side effects, like changes in monsoon patterns, changes in regional rainfall, and the worst-case scenario where one region has cooler summers and another loses important rains. The models say that the eclipse experiment is too small to cause that much trouble. The brain hears “too small” and thinks, “So it’s safe, right?”

Let’s be honest: no one really reads 200-page reports on the effects of the environment before making a decision about the sky.

That’s where the gap between generations gets bigger. People who are older remember a time when science was mostly about things you could touch, like vaccines, microwaves, and the Concorde. You trusted the expert in the white coat because life got visibly better. Younger people grew up with climate graphs, smoke from wildfires, and stories about “unintended consequences.” Their default question is, “What’s the catch?”

From their point of view, “the same species that burnt the planet now wants admin access to the sun.” And it’s being sold as “data collection.” It sounds a little like letting the person who set the fire do the training for the fire extinguisher.

But for the scientists, not running these tests feels like flying blind in a cockpit that is getting hotter and hotter.

How to watch the eclipse without going crazy or losing your trust

So what can a normal person do besides doomscroll? Oddly enough, the first step is very simple: make the eclipse a part of your life again. If you’re in the path, don’t just go along with the experiment; plan your day as a witness.

Get outside with the right eye protection, a cheap pinhole projector, kids, neighbours, or anyone else who is there. Pay attention to how the air cools, how birds act, and how the light feels on your skin. Put it in writing. Put it on tape. Make your body and your notebook into small measuring tools.

When the sky can be programmed, your senses become more important, not less.

The second step is to clean up your mind. There will be viral posts saying “they turned off the sun” and technical PDFs saying “negligible impact.” There is a messy middle in reality that no one has time to read. It’s easy to go from trusting someone completely to being very paranoid.

Ask the boring questions, though. Who pays for the experiment? Who gave it the green light? Are there people who aren’t part of the team running it who can watch? Have people in the communities along the path of the eclipse had any say, or do they just find out after the fact?

We all know how it feels to find out that a big choice about your future was made in a room you weren’t invited to.

At a tense public meeting in Mexico, a young woman stood up and said:

“If you can make the sun less bright for science today, what’s to stop someone from doing it for money tomorrow?”

The room got quiet, not because anyone had an answer, but because the question cut through the PowerPoints.

Her worry is similar to three big issues that people keep bringing up:

Scientists, governments, businesses, or someone else decides when and where the sky gets “tuned.”

What if a “temporary test” makes it necessary to make a permanent tool when climate disasters get even worse?

How do we stop geoengineering from becoming an excuse to delay cutting emissions in the first place?

You can’t call the sun on the phone. Only slow, messy, public talks like that one.

A generation split under the same dark sky.

The arguments will stop for a few minutes when the moon finally takes a big bite out of the sun. Screens will tilt up, babies will squint at the strange half-light, and pets will get confused. The air will get colder. Some of that chill will be natural, and some will be changed slightly by the invisible aerosols that ride wind currents miles above.

No one will care who signed which permit for a few breaths. People will feel very small and very aware that they are standing on a rock that is circling a star. Then the light will slowly come back, along with the questions.

What should we do with a species that can block out its own star? You can call it arrogance or a survival instinct. It could be both.

Main point Detail: What the reader gets out of it

Solar “dimming” is real. Scientists want to release reflective aerosols during the longest eclipse of the century to slightly lower the amount of sunlight that hits the path.It helps you figure out what the headlines mean and what is an experiment and what is full-on geoengineering.

Ethical problemsPeople argue about who gets to control the sky in a warming world, consent, and long-term risks.Gives you words to talk about your fears without going too far into conspiracy or blind faith.

What you need to do as a witnessWhen you observe, write down, and ask grounded questions, you go from being a passive subject to an active participant.Gives you a way to respond that is useful, not just scared or resigned.

Frequently Asked Questions:

Question 1: Are scientists really “dimming the sun” for this eclipse, or is that just a headline?

Answer 1The plan is to do a small experiment by releasing aerosols high in the atmosphere along parts of the eclipse path. This will make the sky a little less bright and let scientists see how the climate reacts. It doesn’t turn off the sun, but it does change the way sunlight comes in to certain areas on purpose.

Question 2: Can this kind of solar dimming really cool the Earth over time?

Answer 2: Yes, in theory: reflecting more sunlight could lower global temperatures, just like big volcanic eruptions have done for a short time. In reality, it’s dangerous, varies by region, and doesn’t address the main problems, like CO₂ in the air or acidification of the ocean.

Question 3: Is it dangerous for people who live in the path of the eclipse?

Answer 3The official line is that there aren’t many direct health risks, and the levels of particles are much lower than what you would find in most cities. The bigger worry is the long-term effects on the climate if these methods are used on a larger scale, not the short-term harm that happens during the test.

Question 4Who is in charge of these geoengineering tests?

Answer 4: Right now, a mix of universities, research institutes, and national agencies are in charge of them, but the rules are not very clear. Many ethicists and activists are worried that there is no one global authority.

Question 5: What can regular people do about all of this?

Answer 5: Read independent news, back campaigns for openness, ask local leaders how your country is involved, and use events like this eclipse as a chance to talk about and record what happens, not just freak out. Public pressure is often the only thing that stops “solutions” from going too far.